Marx seems to have developed an early interest in Spanish in the 1840s, but it was only in the early ’50s that he systematically devoted himself to it. In 1853, he mentioned that he borrowed a concise Spanish grammar book from a friend. In 1854, he reported to Engels on his readings in Spanish and Italian:

At odd moments I am going in for Spanish. Have begun with Calderón.… I am reading in Spanish what I’d found impossible in French, Chateaubriand’s Atala and René, and some stuff by Bernardin de St-Pierre. Am now in the middle of Don Quixote. I find that a dictionary is more necessary in Spanish than in Italian at the start. By chance I have got hold of the Archivio triennale delle cose d’ltalia dall’avvenimento di Pio IX all’abbandono di Venezia [Three-year archive of Italian affairs from the time of Pius IX to the abandonment of Venice] etc. It’s the best thing about the Italian revolutionary party that I have read.

Marx’s immersion in Spanish helped him exploit original sources on Spain’s recent political past. Focusing on the first half of the nineteenth century, he was making preparations to write a series of articles for the New York Tribune. Looking back at his preoccupation with Spanish in previous months, he wrote that “I made a timely start with Don Quixote.… At least it may be counted a step forward that at this moment one’s studies are paid for.” One such payoff was that, in the Spanish sources, he could find ample evidence for a republican conspiracy in the French army when Napoleon was in command in Spain during the Franco-Spanish War. Much later, Spanish was going to be helpful in his studies of the colonial history of the Americas.

…

As Engels wrote much later, even “Italian is much better suited than French to the dialectical mode of presentation.” This impression was originally addressed to Pasquale Martignetti, who reached out to Engels in 1883, sending him his Italian translation of Engels’s Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Not fluent in German, Martignetti translated Engels’s text from Lafargue’s French version. Writing back to Martignetti in Italian, Engels suggested making significant changes of the Italian text, though he admitted that he was not able to render the whole piece in Italian himself, for “my Italian is imperfect and that I am out of practice.” Martignetti also asked Engels to recommend him language resources to improve his German. Given Engels’s response, Martignetti seems to be familiar with Johann Franz Ahn’s German textbook, which gave special weight to bidirectional translation (between original and target languages) of short passages rather than memorizing vocabulary. Engels responded that he was not familiar with Ahn’s book but shared his own method of learning any language from scratch:

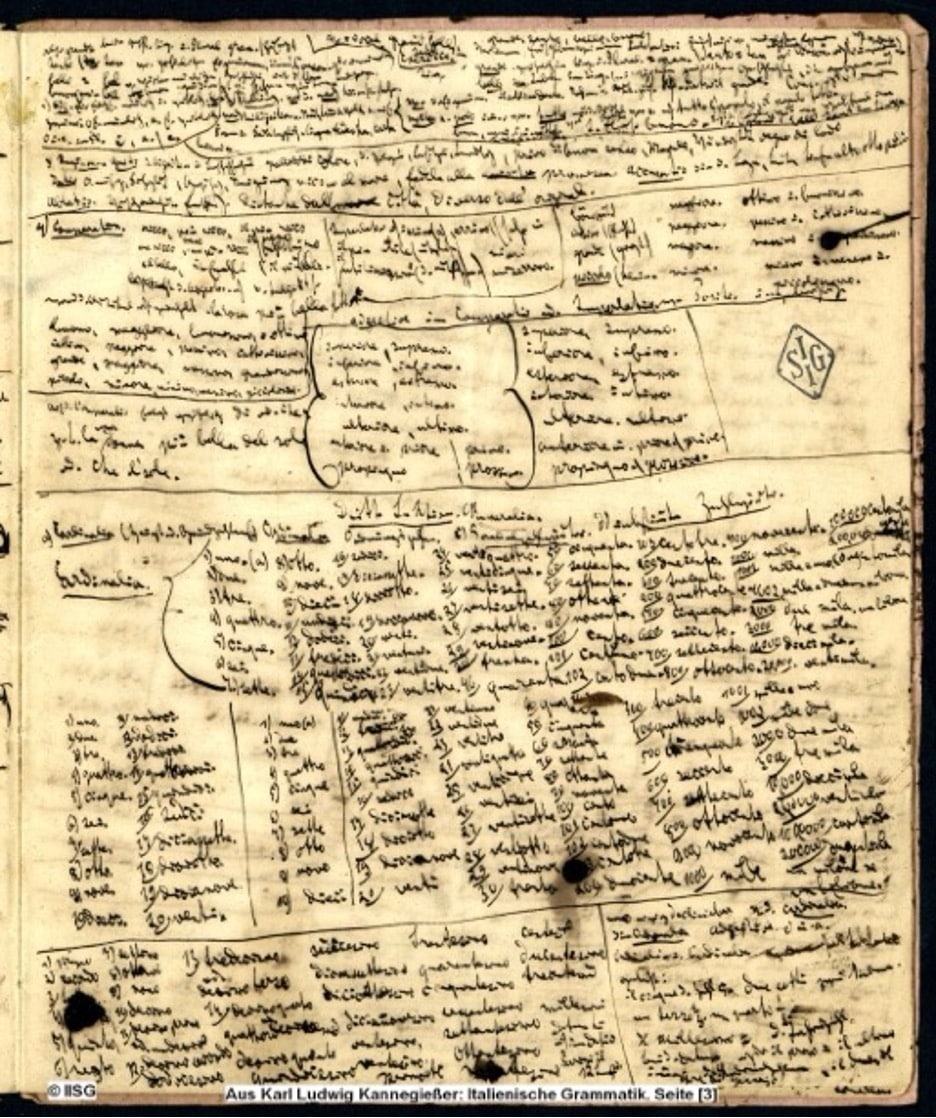

In order to learn a language the method I have always followed is this: I do not bother with grammar (except for declensions and conjugations, and pronouns) and I read, with a dictionary, the most difficult classical author I can find. Thus I began Italian with Dante, Petrarch and Ariosto, Spanish with Cervantes and Calderon, Russian with Pushkin. Then I read newspapers, etc. For German, I think the first part of Goethe’s Faust might be suitable; it is written, for the most part, in a popular style, and the things which would seem difficult to you would also be difficult, without a commentary, for a German reader.

…

It was in the context of political struggles against antisemitism that Engels considered Jewish voices particularly important:

anti-Semitism is merely the reaction of declining medieval social strata against a modern society consisting essentially of capitalists and wage-laborers, so that all it serves are reactionary ends under a purportedly socialist cloak; it is a degenerate form of feudal socialism and we can have nothing to do with that.… Thanks to anti-Semitism in eastern Europe, and to the Spanish Inquisition in Turkey, there are here in England and in America thousands upon thousands of Jewish proletarians; and it is precisely, these Jewish workers who are the worst exploited and the most poverty-stricken. In England during the past twelve months we have had three strikes by Jewish workers. Are we then expected to engage in anti-Semitism in our struggle against capital?

It is unknown to what extent Engels was fluent in Hebrew or Yiddish, but in his very late life, he continued pursuing still other languages, even learning new ones. As he wrote to Laura Lafargue in 1894, he was reading German, English, and Italian daily newspapers and was following various weeklies: “I receive 2 from Germany, 7 Austria, 1 France, 3 America (2 English, 1 German), 2 Italian, and 1 each in Polish, Bulgarian, Spanish and Bohemian, three of which in languages I am still gradually acquiring.”

In his reminiscences of Engels, Lafargue writes that shortly after the fall of the Paris Commune, he had visited the National Councils of the International in Spain and Portugal where he was told that a certain “Angel” (Engels) “wrote perfect Castilian” and “impeccable Portuguese”—”a fine achievement when one thinks of the similarities and small differences the two languages have with one another and with Italian, in which he was equally proficient.”

Edward Aveling recollected that Engels’s home was frequently visited by a large number of socialists from many countries: “Engels could converse with all of them in their own language. Like [Karl] Marx, he spoke and wrote German, French, and English perfectly; nearly as perfectly in Italian, Spanish, Danish, and also read, and could get along with Russian, Polish, and Romanian, not to mention such trivialities as Latin and Greek.”

For Marx and Engels, fluency in reading, writing, listening, or speaking seems to have never been a goal for its own sake. Keen interest in various languages, yes, but always as part of a scientific purpose and political commitment. Socialist internationalism required, and, to some extent, still requires polyglottery.

Basically what I try to do.