The words you are reading have not been produced by Generative AI. They’re entirely my own.

The role of Generative AI

The only parts of what you’re reading that Generative AI has played a role in are the punctuation and the paragraphs, as well as the headings.

Challenges for an academic

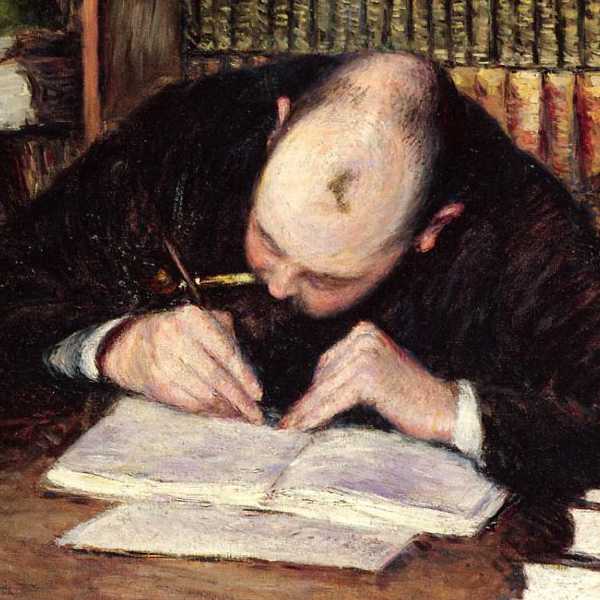

I have to write a lot for my job; I’m an academic, and I’ve been trying to find a way to make ChatGPT be useful for my work. Unfortunately, it’s not really been useful at all. It’s useless as a way to find references, except for the most common things, which I could just Google anyway. It’s really bad within my field and just generates hallucinations about every topic I ask it about.

The limited utility in writing

The generative features are useful for creative applications, like playing Dungeons and Dragons, where accuracy isn’t important. But when I’m writing a formal email to my boss or a student, the last thing I want is ChatGPT’s pretty awful style, leading to all sorts of social awkwardness. So, I had more or less consigned ChatGPT to a dusty shelf of my digital life.

A glimmer of potential

However, it’s a new technology, and I figured there must be something useful about it. Certainly, people have found it useful for summarising articles, and it isn’t too bad for it. But for writing, that’s not very useful. Summarising what you’ve already written after you’ve written it, while marginally helpful, doesn’t actually help with the writing part.

The discovery of WhisperAI

However, I was messing around with the mobile application and noticed that it has a speech-to-text feature. It’s not well signposted, and this feature isn’t available on the web application at all, but it’s not actually using your phone’s built-in speech-to-text. Instead, it uses OpenAI’s own speech-to-text called WhisperAI.

Harnessing the power of WhisperAI

WhisperAI can be broadly thought of as ChatGPT for speech-to-text. It’s pretty good and can cope with people speaking quickly, as well as handling large pauses and awkwardness. I’ve used it to write this article, and this article isn’t exactly short, and it only took me a few minutes.

The technique and its limitations

Now, the way you use this technique is pretty straightforward. You say to ChatGPT, “Hey, I’d like you to split the following text into paragraphs and don’t change the content.” It’s really important you say that second part because otherwise, ChatGPT starts hallucinating about what you said, and it can become a bit of a problem. This is also an issue if you try putting in too much at once. I found I can get to about 10 minutes before ChatGPT either cuts off my content or starts hallucinating about what I actually said.

The efficiency of the method

But that’s fine. Speaking for about 10 minutes straight about a topic is still around 1,200 words if you speak at 120 words per minute, as is relatively common. And this is much faster than writing by hand is. Typing, the average typing speed is about 40 words per minute. Usually, up to around 100 words per minute is not the strict upper limit but where you start getting diminishing returns with practice.

The reality of writing speed

However, I think we all know that writing, it’s just not possible to write at 100 words per minute. It’s much more common for us to write at speeds more like 20 words per minute. For myself, it’s generally 14, or even less if it’s a piece of serious technical work.

Unrivaled first draft generation

Admittedly, using ChatGPT as fancy dictation isn’t really going to solve the problem of composing very exact sentences. However, as a way to generate a first draft, I think it’s completely unrivaled. You can talk through what you want to write, outline the details, say some phrases that can act as placeholders for figures or equations, and there you go.

Revolutionizing the writing process

You have your first draft ready, and it makes it viable to actually do a draft of a really long report in under an hour, and then spend the rest of your time tightening up each of the sections with the bulk of the words already written for you and the structure already there. Admittedly, your mileage may vary.

A personal advantage

I do a lot of teaching and a lot of talking in my job, and I find that a lot easier. I’m also neurodivergent, so having a really short format helps, and being able to speak really helps me with my writing.

Seeking feedback

I’m really curious to see what people think of this article. I’ve endeavored not to edit it at all, so this is just the first draft of how it came out of my mouth. I really want to know how readable you think this is. Obviously, there might be some inaccuracies; please feel free to point them out where there are strange words. I’d love to hear if anyone is interested in trying this out for their work. I’ve only been messing around with this for a week, but honestly, it’s been a game changer. I’ve suddenly looked to my colleagues like I’m some kind of super prolific writer, which isn’t quite the case. Thanks for reading, and I’ll look forward to hearing your thoughts.

(Edit after dictation/processing: the above is 898 words and took about 8min 30s to dictate ~105WPM.)

I think it’s a pretty alright metaphor. My very oversimplified layman’s understanding of dreams and other hallucinations is a nervous system attempting to pattern match nonsense stimulus into something it can recognize, semantics be damned. There are some parallels to draw to a statistical engine choosing the next token based on syntactic probability and forming confidently wrong sentences.

Overly long aside: Even accounting for all the nonsense contemporary LLMs produce, it is quite impressive how much they do get right. I am not opposed to the idea that semantic models such as those of humans and other conscious beings occur as an emergent phenomenon from sufficiently complex syntactic manipulation of symbolic tokens. To me Searle’s Chinese Room thought experiment seems to describe a sentient Choose Your Own Adventure book rather than an unthinking entity, though I’m not sure I even understand the argument properly. I don’t think LLMs have anything I’d describe as a sense of truth, but I’d actually expect the statements of a syntax maximizer to correlate even less with semantically correct ideas and that’s interesting.

Yes, I write like a dweeb but at least I know I’m out of my depth.

The closest thing LLMs have to a sense of truth is the corpus of text they’re trained on. If a syntactic pattern occurs there, then it may end up considering it as truth, providing the pattern occurs frequently enough.

In some ways this is made much worse by ChatGPT’s frankly insane training method where people can rate responses as correct or incorrect. What that effectively does is create a machine that’s very good at providing you responses that you’re happy with. And most of the time those responses are going to be ones that “sound right” and are not easy to identify as obviously wrong.

Which is why it gets worse and worse when you ask about things that you have no way of validating the truth of. Because it’ll give you a response that sounds incredibly convincing. I often joke when I’m presenting on the uses of this kind of software to my colleagues that the thing ChatGPT has automated away isn’t the writing industry as people have so claimed. It’s politicians.

In the major way it’s used, ChatGPT is a machine for lying. I think that’s kind of fascinating to be honest. Worrying too.

(Also more writing like a dweeb please, the less taking things too seriously on the Internet the better 😊)