- 272 Posts

- 8.6K Comments

2·35 minutes ago

2·35 minutes agoOh, that’s interesting. Didn’t know about that.

I don’t think that there’s a way to list instances that a PieFed instance has defederated from, unlike Lemmy; while both have a list of instances at /instances, only Lemmy indicates which ones have been defederated from. It was a helpful tool to help me guess the sort of content an instance had.

Like:

https://lemmy.world/instances (under “Blocked Instances”)

https://piefed.world/instances

EDIT: It does show the last time that the instance sent data, and I guess you could sort of guess that if a large instance that probably has activity hasn’t sent data to the PieFed instance recently — like lemmygrad.ml and hexbear.net on piefed.world — then they’re probably defederated. But it doesn’t clearly indicate that this is the case, either.

2·49 minutes ago

2·49 minutes agoragingHungryPanda

And poop while I was doing it.

looks skeptical

Bamboo is pretty fibrous.

I mean, the bar to go get a reference book to look something up is significantly higher than “pull my smartphone out of my pocket and tap a few things in”.

Here’s an article from 1945 on what the future of information access might look like.

https://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/unbound/flashbks/computer/bushf.htm

The Atlantic Monthly | July 1945

“As We May Think”

by Vannevar Bush

Eighty years ago, the stuff that was science fiction to the people working on the cutting edge of technology looks pretty unremarkable, even absurdly conservative, to us in 2025:

Like dry photography, microphotography still has a long way to go. The basic scheme of reducing the size of the record, and examining it by projection rather than directly, has possibilities too great to be ignored. The combination of optical projection and photographic reduction is already producing some results in microfilm for scholarly purposes, and the potentialities are highly suggestive. Today, with microfilm, reductions by a linear factor of 20 can be employed and still produce full clarity when the material is re-enlarged for examination. The limits are set by the graininess of the film, the excellence of the optical system, and the efficiency of the light sources employed. All of these are rapidly improving.

Assume a linear ratio of 100 for future use. Consider film of the same thickness as paper, although thinner film will certainly be usable. Even under these conditions there would be a total factor of 10,000 between the bulk of the ordinary record on books, and its microfilm replica. The Encyclopoedia Britannica could be reduced to the volume of a matchbox. A library of a million volumes could be compressed into one end of a desk. If the human race has produced since the invention of movable type a total record, in the form of magazines, newspapers, books, tracts, advertising blurbs, correspondence, having a volume corresponding to a billion books, the whole affair, assembled and compressed, could be lugged off in a moving van. Mere compression, of course, is not enough; one needs not only to make and store a record but also be able to consult it, and this aspect of the matter comes later. Even the modern great library is not generally consulted; it is nibbled at by a few.

Compression is important, however, when it comes to costs. The material for the microfilm Britannica would cost a nickel, and it could be mailed anywhere for a cent. What would it cost to print a million copies? To print a sheet of newspaper, in a large edition, costs a small fraction of a cent. The entire material of the Britannica in reduced microfilm form would go on a sheet eight and one-half by eleven inches. Once it is available, with the photographic reproduction methods of the future, duplicates in large quantities could probably be turned out for a cent apiece beyond the cost of materials.

If the user wishes to consult a certain book, he taps its code on the keyboard, and the title page of the book promptly appears before him, projected onto one of his viewing positions. Frequently-used codes are mnemonic, so that he seldom consults his code book; but when he does, a single tap of a key projects it for his use. Moreover, he has supplemental levers. On deflecting one of these levers to the right he runs through the book before him, each page in turn being projected at a speed which just allows a recognizing glance at each. If he deflects it further to the right, he steps through the book 10 pages at a time; still further at 100 pages at a time. Deflection to the left gives him the same control backwards.

A special button transfers him immediately to the first page of the index. Any given book of his library can thus be called up and consulted with far greater facility than if it were taken from a shelf. As he has several projection positions, he can leave one item in position while he calls up another. He can add marginal notes and comments, taking advantage of one possible type of dry photography, and it could even be arranged so that he can do this by a stylus scheme, such as is now employed in the telautograph seen in railroad waiting rooms, just as though he had the physical page before him.

7·3 hours ago

7·3 hours agohttps://www.bostonmagazine.com/arts-entertainment/2016/10/18/puritans-and-sex-myth/

Debunking the Myth Surrounding Puritans and Sex

The Puritans weren’t prudish. In fact, they were passionate.

From the beginning, Puritans maintained sexual intercourse was necessary for procreation, but also asserted sex was an important way for couples to bond in a loving relationship.

“They talk about the duty to desire, that you’re supposed to engage in intercourse with your married partner and that this is good,” says Bremer. “There will actually be some people in early New England who are censured by the church because they have deprived their married partner of sex for three months or more and this is seen as bad.”

51·3 hours ago

51·3 hours agoI don’t think the Puritans had any issue with pregnant people having sex.

The U.S. Navy had (in)famously outlawed alcohol aboard ships in 1914, six years before Prohibition, but it still needed to fill the gap in morale boosting power a sailors daily drink left behind. As any noncommissioned officer who has overseen junior enlisted Americans will tell you: if you don’t give them something to boost their morale, they can get into anything … and you might not like what they find.

Luckily, they found ice cream. Airmen in the Army Air Forces were using open seats on B-17 Flying Fortresses as ice-cream freezers during bombing missions (where temperatures could be as low as -25°F). Navy and Marine Corps aviators would mix canned milk and cocoa powder in fuel drop tanks, then fly missions, returning to their otherwise tropical or desert climates with tanks full of sweet treats.

After an assistant to then-Under Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal wrote that “ice cream, in my opinion, has been the most neglected of all the important morale factors,” the secretary made getting ice cream to those troops his highest priority. Thereafter, any ship large enough would be fitted with a so-called “gedunk bar” (gedunk being the World War II sailor’s word for ice cream, but now just means any junk food). The ice cream had the triple benefit of providing calories, helping beat the heat and boosting morale.

Funderburg writes that by February 1945, at the same time the Allies were preparing to invade Germany in earnest, the Army began building ice-cream factories to bring half-pint cartons “right into the foxholes.”

https://www.thefoodhistorian.com/blog/world-war-wednesday-ice-cream-is-a-fighting-food

By the Second World War, ice cream was firmly entrenched aboard Naval vessels. So much so, that battleships and aircraft carriers were actually outfitted with ice cream machinery, and by the end of the war the Navy was training sailors in their uses through special classes.

QuickCheck: Did a submarine’s crew steal a battleship’s ice cream maker?

Yes, this really happened when the US Navy submarine USS Tang was docked in San Francisco at the same time the battleship USS Tennessee was also in port.

As explained in the Unauthorized History of the Pacific War Podcast by The National WWII Museum staff historian Seth Paridon, ice cream machines were generally only carried by ships like battleships, aircraft carriers, and heavy cruisers with one or more ice cream machines on board.

Paridon then said that the Tang’s skipper - then-Lieutenant Commander Richard O’Kane – gave an order to the sub’s Chief of the Boat, William F. Ballinger, to “go find me an ice-cream maker, by hook or by crook and get it installed aboard this submarine.”

“Ballinger went and ‘liberated’ the ice cream maker aboard the battleship Tennessee that was tied up in San Francisco at that time, and literally just a couple of hours after Tang had shoved off, the shore patrol showed up looking for their ice cream maker that was now aboard a submarine,” he said.

https://www.wearethemighty.com/mighty-trending/navy-tradition-ice-cream-pilots/

The Navy tradition that rewards ice cream for rescued pilots

Imagine you’re a Navy torpedo pilot in World War II. Your life is exciting, your job is essential to American security and victory, but you spend most days crammed into a metal matchbox filled with gas, strapped with explosives, and flying over shark-filled waters of crushing depths. But your Navy wants to get you back if you ever go down, so it came up with a novel way of rescuing you: ice cream bounties.

So, carrier crews came up with a silly but effective way of rewarding boat crews and those of smaller ships for helping their downed pilots out: If they brought a pilot back to the carrier, the carrier would give them gallons of ice cream and potentially some extra goodies like a bottle or two of spirits.

The exact amount of ice cream transferred was different for different carriers, and it seems to have changed over time. But Daniel W. Klohs was a sailor on the USS Hancock in World War II, and he remembered being on the bridge the first time a destroyer brought back a pilot:

I told the captain (Hickey) that it was customary to award the DD with 25 gallons of ice cream for the crew and two bottles of whiskey for the Capt. and Exec. We ended up giving 30 gallons of ice cream because it was packed in 10-gallon containers. This set a new precedent for the return of aviators.

2·9 hours ago

2·9 hours agoDrivers can face a $25 fine, even if there’s no posted signage or painted curb

It seems like it’d help avoid a lot of confusion, especially with drivers who may not live in the city, to paint the curbs.

1·9 hours ago

1·9 hours agoCalifornia’s residential electricity rates are on the order of twice the norm for the contiguous United States. Bring those down, and using electric vehicles will be more appealing.

8·9 hours ago

8·9 hours agoExpect a bunch of people in comments who will deliberately recommend default Arch

Arch

Any of them that use the Arch repos directly are probably fine. Don’t use Manjaro.

Manjaro or Endeavour.

Just base arch

Garuda

Steamos

Artix + OpenRC

CachyOS

EndeavourOS and nothing else.

I suppose that pretty much covers the full gamut.

EDIT: Here’s the Linux distro family tree:

https://github.com/FabioLolix/LinuxTimeline/releases

It lists 19 still-living Arch-based distros. Disregarding category-based recommendations and looking only at explicitly-named recommendations, as of this writing, you’ve explicitly been recommended 7 so far, or over a third of what exist. :-)

You’re right, sorry! It wasn’t indexed here.

https://lemmy.today/pictrs/image/9b037887-82cd-4fa1-b03b-3c3af442e92a.jpeg

2·14 hours ago

2·14 hours agoThe Brits did not have the benefit of knowing just how constrained the German military was, and all of their prior estimates had just fallen apart in France, so a bit of preparation was not, perhaps, entirely amiss.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Sea_Lion

As a precondition for the invasion of Britain, Hitler demanded both air and naval superiority over the English Channel and the proposed landing sites. The German forces achieved neither at any point of the war.

The Battle of Britain was about achieving that air superiority. At the time, both the British and Germans thought that Germany was closer to achieving this than was actually the case.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Britain#Attrition_statistics

Throughout the battle, the Germans greatly underestimated the size of the RAF and the scale of British aircraft production. Across the Channel, the Air Intelligence division of the Air Ministry consistently overestimated the size of the German air enemy and the productive capacity of the German aviation industry. As the battle was fought, both sides exaggerated the losses inflicted on the other by an equally large margin. The intelligence picture formed before the battle encouraged the Luftwaffe to believe that such losses pushed Fighter Command to the very edge of defeat, while the exaggerated picture of German air strength persuaded the RAF that the threat it faced was larger and more dangerous than was the case.[269] This led the British to the conclusion that another fortnight of attacks on airfields might force Fighter Command to withdraw their squadrons from the south of England. The German misconception, on the other hand, encouraged first complacency, then strategic misjudgement. The shift of targets from air bases to industry and communications was taken because it was assumed that Fighter Command was virtually eliminated.[270]

How to look it up:

M-x org-mode RETThat’s “Meta-X” (Alt-X), then “org-mode” and Enter, switches the major mode of the current buffer to org-mode so that we have the org-mode keybindings active.

C-h k C-c C-x C-lC-h, Control-H, is the “help” prefix. “C-h k” isdescribe-key, tells you what a given key sequence runs.C-h k C-c C-x C-lwill say whatC-c C-x C-ldoes. It gives the following output:C-c C-x C-l runs the command org-latex-preview (found in org-mode-map), which is an interactive native-comp-function in ‘org.el’. It is bound to C-c C-x C-l. (org-latex-preview &optional ARG) Toggle preview of the LaTeX fragment at point. If the cursor is on a LaTeX fragment, create the image and overlay it over the source code, if there is none. Remove it otherwise. If there is no fragment at point, display images for all fragments in the current section. With an active region, display images for all fragments in the region. With a ‘C-u’ prefix argument ARG, clear images for all fragments in the current section. With a ‘C-u C-u’ prefix argument ARG, display image for all fragments in the buffer. With a ‘C-u C-u C-u’ prefix argument ARG, clear image for all fragments in the buffer.

I mean there’s the EWMM, emacs based windows manager. So it can absolutely do anything.

Nobody’s made a Wayland compositor running in emacs yet, just an X11 window manager!

EDIT: Okay, apparently they have, ewx, but unlike EXWM, it’s not really in a usable state.

And edit videos.

In order, all of the “Hamster Huey” strips:

https://picayune.uclick.com/comics/ch/1988/ch880710.gif

https://picayune.uclick.com/comics/ch/1988/ch881221.gif

https://picayune.uclick.com/comics/ch/1989/ch891223.gif

https://picayune.uclick.com/comics/ch/1992/ch921006.gif

https://picayune.uclick.com/comics/ch/1993/ch930625.gif

6·5 hours ago

6·5 hours ago

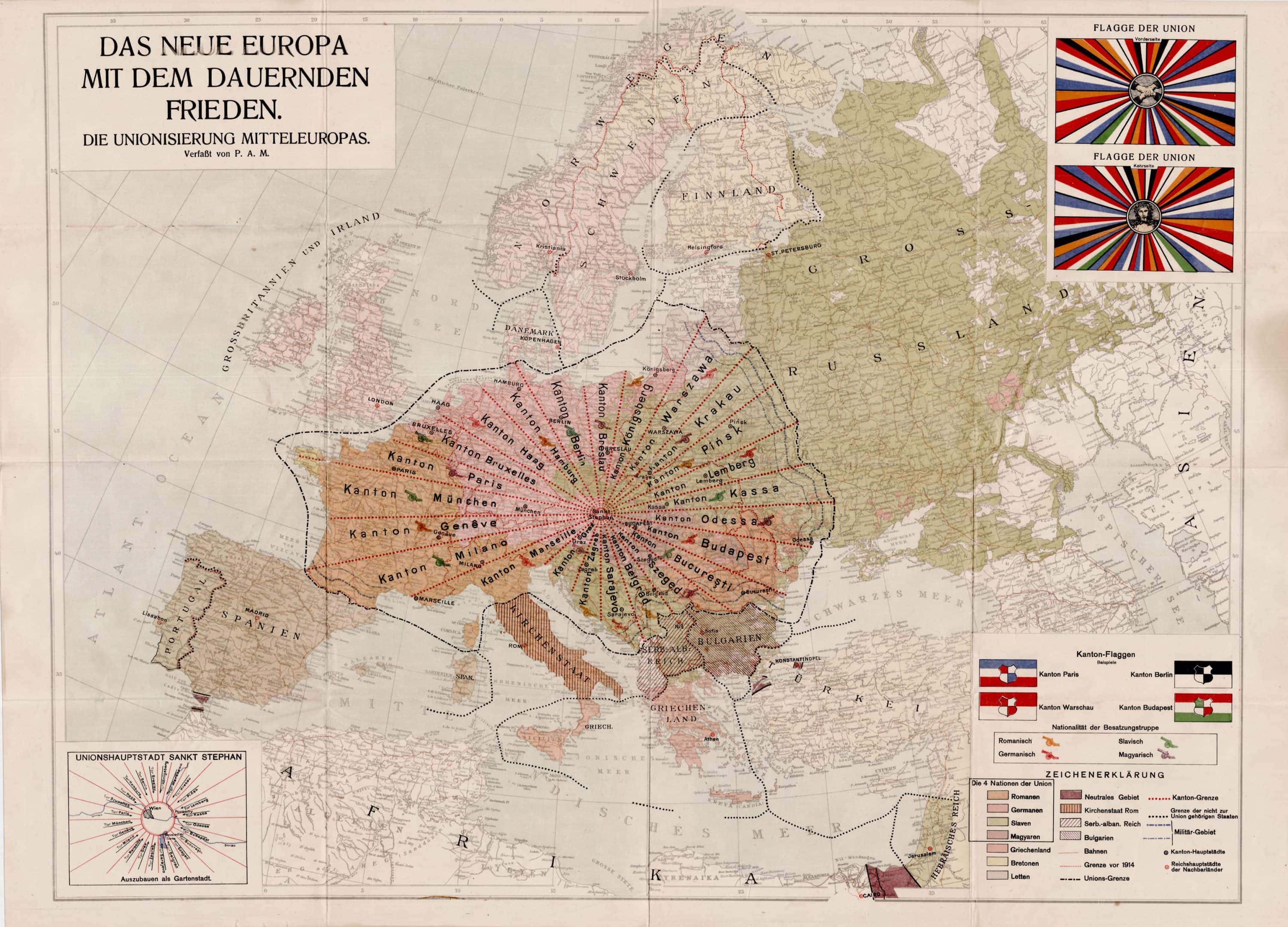

A 1920 pre-European-Union proposal to partition Europe into a set of radial political divisions centered on Vienna. I saved it to submit it to !map_enthusiasts@sopuli.xyz as part of a larger thread.

2·1 day ago

2·1 day agoAgreed.

IIRC, they no longer print it, but you can probably buy used collections.

kagis

Yeah. The final print edition was 2010:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclopædia_Britannica

Copyright (well, under US law, and I assume elsewhere) also doesn’t restrict actually making copies, but distributing those copies. If you want to print out a hard copy of the entire Encyclopedia Britannica website for your own use in the event of Armageddon, I imagine that there’s probably software that will let you do that.