cross‐posted from: https://lemmygrad.ml/post/691946

Do the Middle Ages have minimal relevance to modern history? Contrary to first impressions, maybe not. Research indicates that anti‐Jewish sentiment from the mediaeval period never fully faded away, and only made the NSDAP’s job of attracting support easier:

Churches from Cologne to Brandenburg displayed (and many still display) a Judensau, the image of a female pig in intimate contact with several Jews shown in demeaning poses. The same type of sculpture can also be found in Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, France, and the Low Countries.

[…]

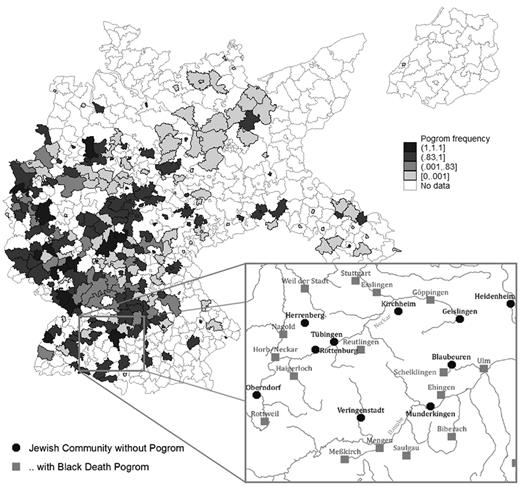

Before turning to the regression results, we examine differences in various twentieth‐century outcome variables between cities that did and did not experience Black Death pogroms. As Table IV shows, pogroms in the 1920s were substantially more frequent in towns with a history of medieval anti‐Semitism.

Similarly, vote shares for the Nazi party (NSDAP) in 1928 and for the anti‐Semitic DVFP in 1924 (when the Nazi Party was banned) were more than a percentage point higher—which is substantial, given that the average vote shares were (respectively) 3.6% and 8%.

Our three proxies for anti‐Semitism in the 1930s also show marked differences for towns with Black Death pogroms: the proportion of Jewish population deported is more than 10% higher, letters to the editor of Der Stürmer were about 30% more frequent, and the probability that local synagogues were damaged or destroyed during the Reichskristallnacht of 1938 is more than 10% higher.

I would like to use this topic to talk more about premodern anti‐Judaism’s influence on Fascist antisemitism. Click here for more.

One notable practice borrowed directly from the Middle Ages was forcing Jews to wear badges. Quoting Sara Jablona’s Badge of dishonor: Jewish Badges in medieval Europe:

Jewish badges, gone from Europe for more than a hundred years, were revived by the [Third Reich] in the twentieth century. [The Third Reich] began a formalised campaign of Jewish stigmatisation blaming Jews for [the Second Reich’s] loss in the First World War, a weak economy, and other societal ills. In 1941, the [Third Reich] ‘imposed on all Jews over six years of age the permanent wearing of a six‐pointed star, ‘Judenstern’, outlined in black on yellow cloth’ (Kisch, 1957, p. 124) (Figure 3).

This badge shaped as the Star of David, or Jewish star, was implemented in every country under [Fascist] authority including most of the countries that had forced Jews to wear badges during the Middle Ages. Once again a stigma symbol, the badge was used not only to humiliate Jews, but also to identify them so as to avoid ‘unlawful intercourse’ between Jews and non‐Jews (Kisch, 1957, p. 130).

The similarity of this badge to the medieval badge was not a coincidence. Kisch (1957) noted that ‘the key to the motives for [re]introducing the yellow badge officially and for [re]applying it to the entire Jewish population is readily found in Anti‐Semitism in the Late Middle Ages’, a book by Wilhelm Grau, the ‘[Fascist] expert on Jewish history’ (p. 127) and head of the Institute for Research on the Jewish Question (Raub und Restitution, n.d.).

Comparing the two eras, Kisch (1957) found many parallels but acknowledged that the [Third Reich] created a situation ‘entirely different from that in the Middle Ages’ (p. 124). Though virulently anti‐[Jewish], medieval Catholic clerics repeatedly warned Christians that Jews were not to be entirely eliminated (Shamir & Shavit, 1985). For the [Western Axis], however, their prime purpose was ‘to eradicate the Jewish community’ (Kisch, 1957, p. 124).

The badge laws of the Middle Ages were meant to segregate and discredit Jews in the course of normal social interactions, while those of the [Third Reich] were intended to identify those to be exterminated.

The ancient theology, now thankfully less common, that ‘the Jews’ murdered J.C. lead to anti‐Jewish tales and serious accusations that Jews—who apparently had nothing better to do with their time—reenacted J.C.’s crucifixion on paintings, statues, figurines, effigies, hosts (consecrated wafers), and most infamously, Christian children. To my surprise, the Fascists did, on occasion, recycle accusations of both host and image desecration. Quoting David I. Kertzer’s In the Name of the Cross: Christianity and Anti‐Semitic Propaganda in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy:

Nor did La difesa fail to make regular use of the most medieval Christian charges against the Jews, with several articles devoted to the Jewish ritual murder of Christian children, along with one on the Jewish profanation of the Host.

A name that stands out among the authors of these articles is Giorgio Almirante, who would later serve as longtime head of Italy’s postwar neo‐fascist party, the Movimento Sociale Italiano. One article he wrote featured an image of two women, one of whom holds up a cross. Its label reads: “These two Polish Jewish women […] are caught by a German soldier in the act of mocking and profaning the symbol of Christ.” Almirante added, “Catholics and fascists might usefully reflect on this image: Rome has no other enemy in the world than Judaism.”⁴¹

Related to the charges of host desecration were the rumours of Jews engaging in literal well‐poisoning. Many Christians in medieval Europe lived in close corridors, considered cleanliness a sign of pride, and upset the environment by harming animals that they associated with both paganism and Judaism. Jewish cultures, in contrast, have consistently valued cleanliness (the proverb ‘cleanliness is next to godliness’ might even have a Jewish origin), so when Christians fell ill while Jews did not, it lead credence to rumors of Jews poisoning wells. This libel also reappeared in some Fascist propaganda. Quoting Sandro Servi in The Jews in Italy under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922–1945, pg. 127:

Accompanying an article bylined “C.B.” (possibly Carlo Barduzzi) about “Jews (giudei) and Arabs in Medieval Spain,” in issue number 16, year III (June 20, 1940), there appeared, without any explicit relationship to the text, an illustration with the caption, “Jews (giudei) Poisoning Wells” (Figure 4). The accusation that Jews poisoned wells spread in France during an outbreak of the plague.⁴²

The Jews, inspired by the devil and in cahoots with the Moors of Granada, supposedly made a pact with the lepers to destroy Christians by infecting well‐water by tossing little bags of blood, urine, herbs, and consecrated Hosts into them.

Likewise, image desecration almost certainly influenced blood libel, something that the Fascists recycled frequently (even though Deuteronomy 12:21–24 explicitly commands its readers not to ingest blood):

Some Fascists went so far as to claim that J.C.’s death was itself a ritual murder! Quoting David I. Kertzer’s & Gunnar Mokosch’s The Medieval in the Modern: Nazi and Italian Fascist Use of the Ritual Murder Charge:

Der Stürmer cast Christ’s crucifixion as a case of Jewish ritual murder. In an advertisement for its special April 1937 issue on “Judaism vs. Christianity,” the paper claimed Christ to be “one of the biggest enemies of the Jews of all times,” and his death on the cross “the greatest ritual murder of all times.”

An article on an alleged recent ritual murder in Palestine made explicit the connection between the crucifixion of Jesus and Passover murders: “Every year, when Nature awakes and the peoples celebrate the new year of Life, wherever Jews live something terrible happens. To symbolically feed their desert idol, the people‐devouring Jehovah, they have to sacrifice one of the best of the goyim. To better relish the Passover lamb. Thus was Jesus of Nazareth slaughtered.”

The European Fascists eagerly exploited the theology that ‘the Jews’ were to blame for J.C.’s death. The Chancellor hisself referenced it, and Julius Streicher claimed that ‘The murder of Golgotha is written on the foreheads of the Jews’ and that ‘The Jews betrayed Christ. They committed a ritual murder on Golgotha.’ A 1929 Der Stürmer cartoon featured a caricature saying ‘One can do anything to those Goyim. Our people crucified their Christ on the cross, and we do a great business on his birthday…’ It was visible in Passion plays during (and long before) the Fascist era, and Fascist children’s books such as Der Giftpilz and Trau keinem Fuchs auf grüner Heid und keinem Jud auf seinem Eid also disseminated this ancient accusation, even though it was already well entrenched:

[T]here was an SS man there, SS people, who had told me how they had come to do it voluntarily, compulsorily, it was certainly not simple to explain. In Austria, for example, people, young men, were brought into the SS during ’44 whose fathers had been killed in the camps, so that was going on too, you know. But the typical thing was a talk with an SS man who said, ‘Well, we grew up like that. The priest, that is the clergyman who gave us instructions, he said, ‘Well, it was the Jews who killed Christ, you know.’’ And so that stuck in our minds, of course, and for all the others too. That is not the explanation, but that was his, uh…

Justification?

…justification, that the others had told him that the Jews were guilty something, namely of the murder of Christ, although the people were really not at all pious, so you can’t say that was the reason for it, but that was an explanation for him. A justification for him.

Never mind how the Gospels strongly implied that the hanged one was Jewish (which most of the Fascists denied), or how the death was a self‐sacrifice (John 10:17–18), or how he asked his father to forgive the assistants (Luke 23:34), or how the death lasted no longer than three days, or that without the death, there would be no eternal life for Christians anyway (which would arguably make any Jew’s rôle in it an honour rather than a dishonor). Never mind any of that. For Christian xenophobes such as the Crusaders and the many Fascists who took inspiration from them, any Jew’s involvement in J.C.’s execution supplied a handy excuse to persecute contemporary Jews who could not possibly have had anything to do with it.

Another cliché inherited from the First Reich and Europe in general was the legend of the Wandering Jew, Ahasuerus (or Ahasver). Ahasuerus had purportedly mocked J.C. on the way to his execution, who responded by cursing him to wander the Earth until the Second Coming. The Fascists referenced Ahasver repeatedly in generic propaganda and occasionally in tales, but unlike in the premodern era, it seems that they never meant for this to be understood literally, only symbolically. One example:

The Jews complain about us? They should thank the democracies that put them in their admittedly unpleasant situation! Where are the democratic nations ready to receive them without condition?

As far as we are concerned, they can wring their hands in their lifeboats until they look like old washer women. We do not care if ships sail the oceans and find no harbor. Ahasver has been moving around the world since a bit longer than 1933 without finding rest. Did we send him on his way?

‘Ahasver’ represents Jewry, somewhat analogous to how ‘Ivan’ represents Russians.

The association between Jews and finance was due to the increasingly limited opportunities that Europe’s mediaeval authorities offered them. Christians considered usury to be unexceptionally sinful, yet many rulers knew that it was sometimes necessary, so they kept financial professions open to Judaists since they were damned anyway. Quoting Christopher Tuckwood’s From Real Friend to Imagined Foe: The Medieval Roots of Anti‐Semitism as a Precondition for the Holocaust:

Money was not yet a major feature of the European economy in the ninth and tenth centuries, so finance and moneylending had not yet become major occupations for Jews, particularly since no other occupations had yet been completely closed to them. However, a “Capitulary for the Jews” by Charlemagne in 814 indicates that some did lend money to a degree, as it bans them from taking “in pledge or for any debt any of the goods of the Church” or “to take any Christian in pledge.”²⁰

It was common practice at the time for a borrower to offer his freedom as collateral and, if he defaulted on a loan, to be taken into the custody of his creditor either as a hostage or a slave. This law of Charlemagne was likely a Church‐inspired attempt to reduce Jewish control over Christians. Soon after, the Jewish right to own even non‐Christian slaves was limited, removing them from their earlier pre‐eminence in the slave trade and severely limiting their ability to participate in large‐scale agriculture.

The loss of this right alone had major ramifications and caused later long‐term implications for the economic lives of France’s Jews. Their decline had begun.

[…]

The majority of Jews still scratched out livings in low‐level occupations, but the minority who did move into moneylending was a highly visible one. These Jewish financiers inadvertently formed the seed of the stereotype of the “money‐loving Jew,” which has found incredible longevity and fame. Medieval Christians found it especially easy to associate all Jews with moneylending since, relative to the Christian majority, a greater proportion of the Jewish community were moneylenders even when Christians made up the majority of lenders overall.

Hence, Christian xenophobes (e.g. William Dudley Pelley) believed that the vendors and money‐changers in J.C.’s temple must have been Jews, and they saw Judas Iscariot’s infamous betrayal for thirty pieces of silver as a confirmation of his Jewishness.

23·6 months ago

23·6 months ago